Architect James Meyer Brings His Business Home with a New Eponymous Identity and Streamlined Approach

Blueprint for a beautiful life.

-

CategoryArchitecture, Homes + Spaces

-

Written byMichele Garber

-

AboveJames Meyer. Photographed by Jeff Berting.

That James Meyer is the creative force behind some of the Los Angeles area’s most beautiful homes and spectacular commercial developments is enough to make him a fascinating subject. Yet after spending just a few moments with him, it’s clear that what makes his story compelling goes far deeper than merely the sum of his work.

James is a talented designer and builder, to be sure. Yet he is also a creative spirit, a mentor, a loyal colleague and a devoted family man. He is direct, gentlemanly and magnanimous. His depth and sincerity permeate all his interactions. He is candid and unafraid to let his sensitive side show.

A consummate professional with integrity, an unrivaled work ethic, meticulous attention to detail and an ability to lead and make tough decisions, James embodies the essential character needed in someone entrusted with multimillions of dollars and time-sensitive projects.

Born in Cleveland, Ohio, on December 18, 1969, James takes pride in being born in the ’60s—albeit in its last two weeks. He admires the decade for what was happening “culturally, artistically and musically” and views it as a time of self-expression, freedom and creativity—hallmarks of his character.

James has many other creative interests beyond design and architecture. He is a burgeoning chef, a writer and a musician. So he is equally proud that he shares his birthdate with the incomparable Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones.

When James was a toddler, the Meyers moved from Cleveland to Torrance. Growing up a native Angeleno greatly influenced him. “I was shaped by the Southern California lifestyle and wild freedoms that came to define my generation,” he says. “I cannot imagine a more impactful place to grow up than in L.A.”

The tight-knit Meyer family shared a common sense of adventure, kindled by James’ parents, Jeanne and Jim. The family fully embraced their cross-country move and together experienced all that California had to offer.

James’ father had served on a Naval aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean in the early ’60s and developed an unquenchable curiosity for travel, culture and international cuisine. He ferried James and his siblings all over the southland to experience the character and delicacies of L.A.’s diverse tapestry of international neighborhoods.

Even when he was young, James had a heightened aesthetic sensibility, and many around him noticed his discerning eye for design. Among those was Maren Blyth, the mother of James’ close friend Jesse. Maren, a collector of contemporary art and mid-century furnishings, had strong connections in the art world. The stylish decor of the Blyth’s Hermosa home made an impression on James, and the precocious adolescent let Maren know that he admired her “exquisite” taste.

Wanting to encourage his blossoming artistic inclinations, Maren auspiciously took Jesse and James to a party at the Santa Monica home of architect Clelio Boccato. Clelio was an associate of revered architect Ray Kappe, who was both the original founding chair of the Department of Architecture at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and founding director of the esteemed Southern California Institute of Architecture.

Maren must have primed the artists and architects in attendance that day, as they not only welcomed young James with open arms but also initiated him into their world by giving him a tour of the handsomely appointed mid-century modern home Clelio had designed. The precise moment that truly changed the trajectory of James’ life came when he met Clelio’s brother, Peter Boccato, a well-respected architect in his own right.

Peter said to 13-year-old James, “I understand that you would like to be an architect someday.” Though James knew virtually nothing about architecture nor was he thinking about his future career or whether he would attend a university, he enthusiastically replied, “Yes I would.”

Peter then suggested that if James was serious about becoming an architect, “he must attend the College of Architecture & Environmental Design at California Polytechnic in San Luis Obispo.” At that exact moment, the die was cast.

“That afternoon I had decided not only that I would attend college, but I knew exactly where I would be going and that nothing would be getting in my way,” James explains.

Indeed James would earn his degree in architecture from Cal Poly SLO. But years before that achievement, he pursued another challenging goal with a level of commitment and tenacity that sheds brilliant light on his true character.

Throughout his youth, James participated in Scouting. Even today, the 12 points of the Scout Law roll easily off his tongue and have served as guideposts for how he has conducted his life.

“I always had an immense respect for the military and the veterans in our country. And I was the first one in my family’s history that didn’t serve in the military,” James explains. “My time in the Scouts was an opportunity to learn things outside of what I was learning in school. I embraced outdoorsmanship, backpacking, camping, wilderness survival. My parents weren’t into camping, so my whole experience in being connected to the outdoors was all through Scouting.”

James was close to his paternal grandfather, Robert, who was an Eagle Scout in the 1930s and always carried a 1932 official Boy Scouts of America pocketknife that James admired. One day his Grandpa Bob told him that if he too became an Eagle Scout, he would give him his coveted pocketknife.

“My grandfather was this awesome guy. He really lived life, he was a pilot, traveled the world, did all kinds of cool things. I admired him,” says James. “When he offered to give me the knife if I became an Eagle Scout, the same way I committed to going to architecture school, I became obsessed and focused on becoming an Eagle Scout.”

James achieved that goal in 1986, a year after his grandfather suffered a stroke and became reliant on a wheelchair. But that didn’t stop his grandfather from flying out for the ceremony. “My grandfather got up on the stage in his wheelchair, then he got out of the wheelchair and presented me with the pocketknife … there wasn’t a dry eye in the house. It was incredible, and I will always remember that.”

James adds, “At an early age I made a decision to commit to something and to make it happen. I still to this day pursue everything with the same vigor. Once I get my teeth onto something, it’s hard to yank it out of my mouth,” jokingly he adds, “like an old dog.”

Ironically, the grit and tenacity that led James to become an Eagle Scout and pursue a degree in architecture at Cal Poly didn’t directly translate into him becoming an architect. He readily admits that when he graduated from Cal Poly SLO—one of the country’s preeminent architecture programs—he wasn’t intent on becoming an architect. What he did know was that he’s always had a fiercely independent streak, always liked to build things and wanted to build those things himself so he could do so his own way.

He landed a position at one of the premier architecture firms in the U.S.: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in New York City. It was there that his design talent flourished and he fully realized his passion.

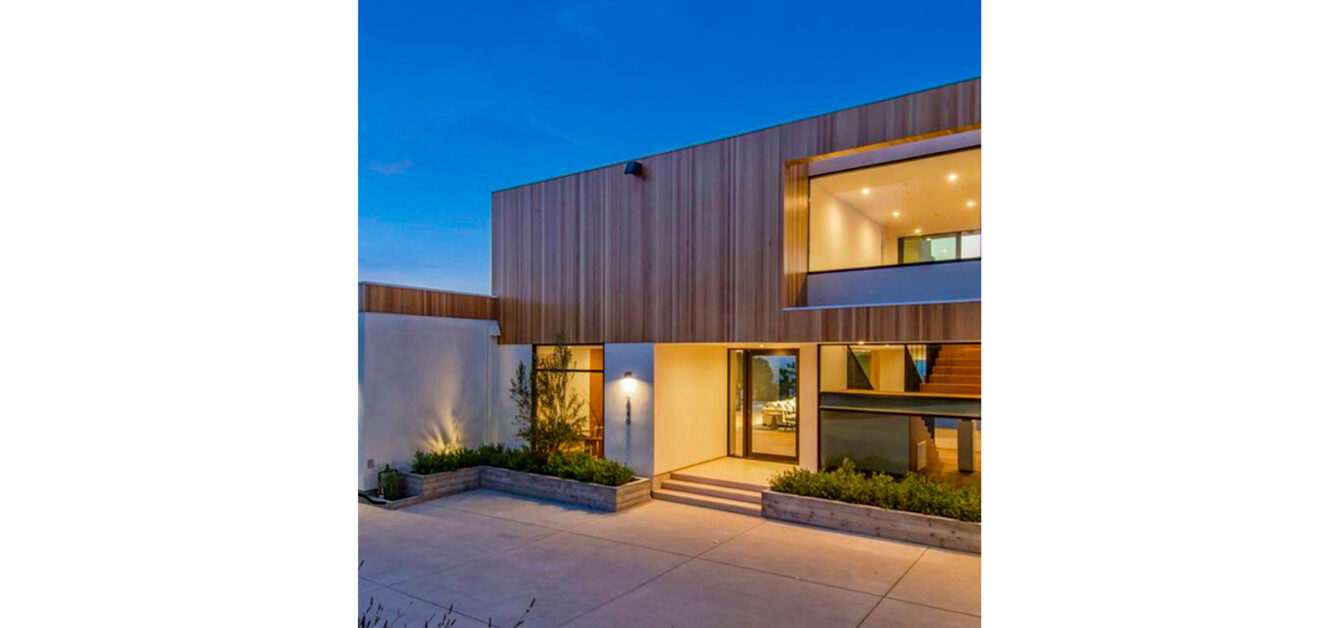

James’ architectural style is eclectic and closely tied to each site and project. “With each project, you are trying to explore new ideas and trying to push the envelope,” he says. “If you were to look at all of our work, you will see common threads throughout the projects. Each is unique and different, but they’re all coming from the same head and the process is the same. There are just different results—which there should be. There are different sites and different personalities and different clients. So I’ve never been one who has embraced a specific style for myself.”

When asked the inevitable and slightly annoying question of whether he has a favorite project, he answers the way most artists would: “It’s very hard to nail down. They’re all great. They’re all my kids.”

Yet when pressed, James shares that one stands out as particularly challenging and noteworthy—not merely for its design but also for its association with Julius Shulman, an artist whom James greatly admired. The home built on Wild Oak Drive in the Hollywood Hills was completed about a year before the famed photographer passed away, and James had the good fortune of meeting, working with and becoming friends with Julius, who photographed the Wild Oak property.

Before establishing his current practice, J R M / A: The Studio For Architecture, in El Segundo, James helmed his architectural design-build practice LEAN ARCH based in Downtown Los Angeles for more than 20 years. He believes strongly in the art of making “places not spaces,” which was reflected in LEAN ARCH’s motto “We Build Places.” The firm’s core principle centered around the design and execution of projects with context, scale and sustainability.

A few years into owning LEAN ARCH, James earned his general contractor license, enabling him to actively build as well as design architectural projects. In addition to the Wild Oak project, under the LEAN ARCH mantle James designed the award-winning Kuhlhaus 01 and Kuhlhaus 02, both in Manhattan Beach.

Some of his notable commercial projects include the State Bar of California in DTLA, Uber’s Santa Monica office and the headquarters for 72andSunny in Playa Vista. That project is of special significance as it transformed the Bauhaus-style historic campus of aerospace maverick Howard Hughes where the infamous “Spruce Goose” was designed. Among its noteworthy features is the use of recycled wood from UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion to build bleachers that form a central meeting area large enough to host the ad agency’s whole team.

So why would James, who is clearly at the top of his game, shake up his architectural practice with a cross-city move and name change? His bold decision to refocus his brand was inspired by a confluence of factors.

Near the end of 2019, James was approaching age 50 and found himself reevaluating his priorities as many do when reaching that milestone age. Years earlier, a longtime friend and fellow architect told him something that still resonates.

“I’ve been reflecting a lot on words of wisdom from a friend of mine, Pat Killen, who was also an architect in the South Bay,” James explains. “He was a brilliant guy, and I really admired him. We had a good friendship and understanding of one another. We always had great conversations. He passed away seven or eight years ago from cancer. He told me that at one time he had a large firm, 30 or 40 people in DTLA, and when he got to be 50 he asked himself, ‘What am I doing? Am I getting everything that I want out of this?’”

James continues, “I used to be obsessive: ‘I have to do this by the time I’m 30, or do this by the time I’m 40.’ Now as I’ve matured as an architect, my attitude has changed. I’d always heard that architects are simmering for a long time; most don’t hit their stride until they’re in their 50s. Usually it takes that long to truly have an understanding of what it is you need and want to do. I’ll always think about what Pat told me. He said, ‘No, I’m not going to do this anymore. I’m going to wind all this down.’ He started a new practice in the South Bay and focused on residential work. It was more about him enjoying the work and enjoying his life. That was really solid advice.”

Just months after James turned 50, the pandemic hit. His agency already had a smaller satellite office in Manhattan Beach since 2010. When his team was forced to work remotely, the idea of relocating the practice to the South Bay began to take shape. “It seemed to me that it was time for me to step out from behind the anonymity of the LEAN ARCH and introduce myself as an architect in a more personal way,” he shares.

Then earlier this year the unthinkable happened. James lost both his mother and his sister within the same month. The passing of his younger sister Diana hit him particularly hard and brought to a boil the thoughts of refocusing his architecture practice that had been simmering for well over a year.

James’ wife, Wimberly, said something that clinched his decision. He is a devoted family man, and one of the considerations leading him to make these changes was his desire to be nearer to home and have more time with Wimberly and their two children. For him, being a good husband and father takes precedence over everything.

“My wife taught me that you need to put yourself into a mindset that allows positive energy to flow into your body,” he shares. “She said, ‘Knock those chips off and be unapologetic for who you are as a person. The good and the bad. Get yourself into a positive mindset.’”

Visibly moved, James tears up as he continues, “It was such profound advice coming from the woman who I love and have the most respect for out of anybody … and her advice has been so wonderful.”

Reflecting on the passing of his mother and sister he adds, “Losing a parent is inevitable, but losing a younger sibling forced me to pause and think about my own mortality, my legacy—especially where my children are concerned. The bigger things that you don’t usually think about. It contributed to this notion of not ever being a bystander, not ever letting a day go by without taking full advantage of that day, getting the most out of everything you do.”

James likens it to author Henry David Thoreau’s words about wanting to “live deep and suck out all the marrow of life” in his book Walden. “I want to be that person. I don’t think I’m there yet, but I want to wake up every day and have an experience that I can be truly proud of when I go to bed at night—whether taking the dog for a walk, enjoying the sunshine, enjoying the sounds and smells around us. The COVID-19 lockdown denied us essential life experiences that we need as human beings: hugs, seeing each other’s smiles.”

James believes his mom and sister are looking down and encouraging him to make the most of things. With J R M / A, he’s certainly striving to do exactly that. For more on James and his practice, visit jamesrmeyerarchitect.com.

Tracing the Legacy of Legendary California Architect Paul Williams

He’s finally getting his due.

The Nation’s First-Ever Cannabis Cafe Will Open in West Hollywood

Lowell Cafe will open its doors on September 1, but not everyone is thrilled.

Get the Latest Stories